Understanding Intervertebral Disc Degeneration: Challenging the “Blown-Out Disc” Myth

- Whitney Lowe

The phrase “blown-out disc” is commonly used to describe intervertebral disc herniations or protrusions. However, this term can be misleading and perpetuate inaccurate perceptions about the underlying pathophysiology of disc degeneration and herniation. As massage therapists, it is valuable to understand the biomechanics of intervertebral discs and the processes that lead to disc pathology to provide appropriate treatment and education to clients.

Intervertebral Disc Structure and Function

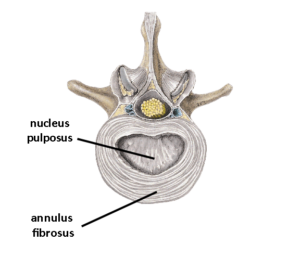

The intervertebral discs are fibrocartilaginous structures located between the vertebral bodies of the spine. They serve as shock absorbers, facilitating movement and distributing compressive loads between the vertebrae. The disc comprises two principle components (Image 1):

- Nucleus pulposus: The central, gel-like core composed of proteoglycans and water, providing the disc’s compressive strength and flexibility.

- Annulus fibrosus: The outer, fibrous ring consisting of concentric layers of collagen fibers, providing structural integrity and containment of the nucleus pulposus.

Disc Degeneration and Herniation: A Gradual Process

Contrary to the “blown-out disc” concept, intervertebral disc herniations or protrusions are rarely the result of a sudden, traumatic event in a healthy disc. Instead, disc degeneration is a gradual process that occurs over time, often due to a combination of factors, including aging, genetic predisposition, and cumulative mechanical stress.

As discs degenerate, they lose hydration, and the nucleus pulposus becomes less gelatinous and more fibrotic. The annulus fibrosus also weakens, making it more susceptible to tears or fissures. These structural changes can lead to disc bulging, protrusion, or herniation, where the nucleus pulposus material extrudes through the compromised annulus fibrosus and potentially impinges on nearby neural structures, causing pain or neurological symptoms.

Biomechanical Considerations

Research on cadaveric lumbar spine specimens has demonstrated that intervertebral discs are remarkably resistant to acute, high-impact forces. Studies have shown that before a disc rupture or herniates, the vertebral endplates are more likely to fracture under extreme compressive loads [1]. This suggests discs are designed to withstand sudden, high-impact forces more effectively than sustained, cumulative stress over time.

Prolonged exposure to sub-optimal postures or repetitive movements can contribute to disc degeneration by altering the biomechanical forces acting on the spine. For example, prolonged sitting in a slumped posture can be more detrimental to the lumbar discs than a single instance of heavy lifting, as it subjects the discs to sustained, uneven compressive loads.

Relationship Between Disc Degeneration and Pain

It is important to note that the presence of disc degeneration or herniation does not necessarily correlate with the experience of pain. Many individuals with disc pathology may be asymptomatic, while others may experience significant pain or neurological symptoms. The relationship between disc degeneration and pain is complex and influenced by various factors, including the extent of disc protrusion, nerve root compression, individual pain perception, and the presence of inflammatory mediators or noxious chemical irritators.

Implications for Massage Therapy

Understanding the biomechanics of intervertebral disc degeneration and challenging the “blown-out disc” myth has essential implications for orthopedic medical massage practice:

- Education: Providing clients with accurate information about disc pathology can help dispel misconceptions and promote a better understanding of their condition. It may also help them have less fear and apprehension about their existing pain complaint.

- Treatment approach: Massage techniques can focus on potential underlying causes of disc degeneration, such as postural imbalances, muscle imbalances, and movement patterns contributing to abnormal spinal loading.

- Collaboration: Working closely with other healthcare professionals, such as physical therapists, chiropractors, and physicians, can ensure a comprehensive and multidisciplinary approach to managing disc-related conditions. The more you understand these conditions, the better you will communicate with your colleagues.

- Preventative strategies: Emphasizing the importance of maintaining proper posture, engaging in regular exercise, and promoting spinal health can help prevent or slow the progression of disc degeneration.

By understanding the biomechanics of intervertebral disc degeneration and challenging inaccurate concepts like the “blown-out disc” myth, massage therapists can provide more informed and effective care for clients with disc-related conditions.

Want to Learn More?

Come check out our course on lumbar and thoracic pathologies to learn more about how to recognize and work with disc pathologies. Visit the course here.

References:

[1] Callaghan, J. P., & McGill, S. M. (2001). Intervertebral disc herniation: Studies on a porcine model exposed to highly repetitive flexion/extension motion with compressive force. Clinical Biomechanics, 16(1), 28-37.

[2] Takatalo, J., Karppinen, J., Niinimäki, J., Taimela, S., Näyhä, S., Järvelin, M. R., … & Lähde, S. (2011). Prevalence of degenerative imaging findings in lumbar magnetic resonance imaging among young adults. Spine, 36(16), 1190-1199.

[3] Cheung, K. M., Karppinen, J., Chan, D., Ho, D. W., Song, Y. Q., Sham, P., … & Luk, K. D. (2009). Prevalence and pattern of lumbar magnetic resonance imaging changes in a population study of one thousand forty-three individuals. Spine, 34(9), 934-940.