Current Concepts in Patellofemoral Pain

- Whitney Lowe

Patellofemoral pain syndrome (PFPS) is a term that describes generalized anterior knee pain around or under the patella. Overactivity and excessive mechanical load on the patellofemoral joint are the leading causes. There isn’t an apparent tissue dysfunction for the pain, but several factors may contribute to the discomfort felt during movement.

Below we discuss key anatomical, biomechanical, and psychosocial factors that play a role in this challenging problem. Massage therapy treatment for PFPS is most successful when the practitioner understands the fundamentals of the joint mechanics, factors in the client’s activities, and lifestyle, and can blend these elements with specific assessment findings to construct a beneficial treatment strategy.

Anatomical Background

PFPS is challenging because it isn’t clear what is causing the pain in most cases.1 However, a good understanding of knee anatomy and mechanics helps identify key contributors to the problem. The first place to start is with the knee extensor muscle group.

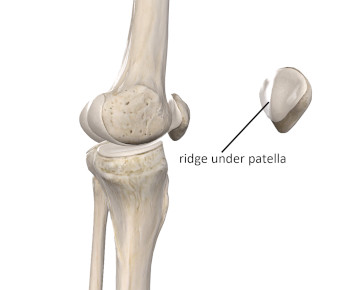

The large and powerful quadriceps femoris muscle group is responsible for knee extension. While extension occurs at the tibiofemoral joint (between the femur and tibia), a third bone, the patella, is an integral part of power generation for this movement. The patella has a bony ridge on its underside (Image 1). That ridge fits in the groove between the two femoral condyles. The patella moves superiorly and inferiorly during flexion and extension, and the bony ridge tracks in a groove formed by the femoral condyles.

Image 1

Ridge on the underside of the patella

Image courtesy of Complete Anatomy

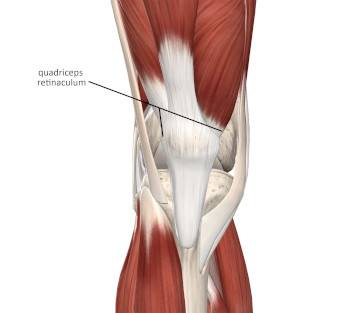

The patella is a sesamoid (floating) bone embedded in the quadriceps (patellar) tendon. Interestingly, babies are born without a patella. The bone develops in the tendon as the baby gradually starts increasing load through weight-bearing and standing. Anatomy books primarily show the four quadriceps muscles blending into the patellar tendon and attaching to the tibial tuberosity. However, force is also transmitted to the tibia by way of connective tissues around the knee that make up the quadriceps retinaculum (Image 2). The quadriceps retinaculum is richly innervated, so it is likely to be a source of pain with mechanical challenges of PFPS.2

Image 2

Connective tissues around the knee

Image courtesy of Complete Anatomy

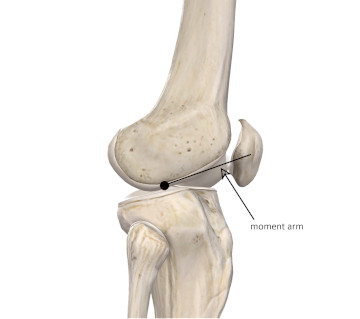

While the patella does offer some protection for the knee, its primary role is improving mechanical function at the joint. Force production at a joint is dependent on a physics principle called the moment arm. So, what on earth is a moment arm (it has nothing to do with time or the upper extremity)? Most joint movements occur around a point called the axis of rotation. Envision an imaginary rod going through the knee joint right at the axis of rotation, with the tibia rotating around that rod during flexion and extension. The moment arm is the length between the joint’s axis of rotation and the line of force that acts on the joint (Image 3). The primary function of the patella is to increase the length of the moment arm for knee extension, which makes the quadriceps more powerful. These higher force loads during knee extension and flexion can also be a contributing factor to patellofemoral pain.

Image 3

The moment arm of joint rotation

Image courtesy of Complete Anatomy

What Causes Patellofemoral Pain?

PFPS is most common in young people, especially those between the ages of 12 and 17 involved in running, jumping, or other vigorous lower extremity activity. Yet, the condition is also prevalent in people throughout all age ranges who suddenly increase activity loads or do something that involves high force loads during knee flexion and extension. Overactivity appears to be the biggest problem.

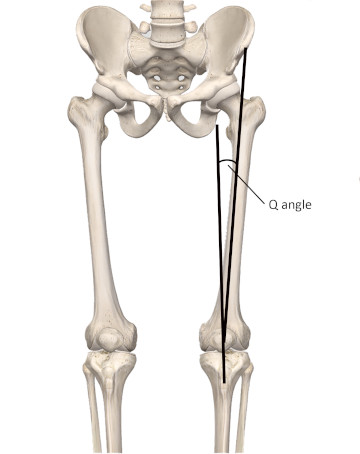

Women develop PFPS more often than men, although the reasons for this are not fully clear. Several factors play a role in that increased incidence. The first is a larger Q angle in women. The Q angle, also called the quadriceps angle, is formed by imaginary lines that connect bony landmarks. One line extends from the tibial tuberosity through the midpoint of the patella. Another line passes from the ASIS to the midpoint of the patella. The angle between these lines is the Q angle (Image 4). The wider is the pelvis, as occurs in females, the larger is the Q angle. The quadriceps pull more laterally when the Q angle is larger and not as much straight up and down. The increased lateral pull from the quadriceps pulls the patella in a more lateral direction, resulting in patellar tracking problems that become a primary factor in the client’s PFPS pain.

Image 4

The Q angle affecting patellar tracking

Image courtesy of Complete Anatomy

There is also an increased incidence of valgus (knock-knee tendency) alignment at the knee in women. The increased valgus alignment also causes the quadriceps to pull more in a lateral direction. Other postural alignments in the lower extremity can also play a role. Increased foot pronation during gait may be another potential cause of alignment and corresponding patellar tracking problems.

Weakness in the hip abductors or external rotators may also contribute to the problem. When the external hip rotators are weak, the femur may be pulled toward medial rotation. With the hip more medially rotated during knee flexion and extension, the patella has a tendency toward lateral tracking. As we can see, most of these alignment problems involve the patella tracking too much laterally and not straight up and down.

The most distal portion of the vastus medialis in the quadriceps muscle group functions to offset the lateral pull on the patella. Because of the oblique orientation of these vastus medialis fibers, this portion of the muscle is called the vastus medialis obliquus or VMO.

PFPS is closely related to another condition called chondromalacia patella. Chondromalacia is softening and degeneration of the articular cartilage. When the patella is repeatedly pulled against the femoral condyles, as in a tracking disorder, it may cause degradation and breakdown of the articular cartilage on the underside of the patella. Cartilage degeneration is evident with grinding or grating sensations of the patella during knee flexion and extension.

Formerly, the pain of patellofemoral pain syndrome was blamed on cartilage degeneration. Yet, the hyaline cartilage under the patella is poorly innervated, so it is unlikely that significant knee pain comes from the cartilage degeneration itself in PFPS. However, just under the cartilage is a layer of richly innervated subchondral bone. Pain could certainly result from friction of the subchondral bone.

The biomechanical factors mentioned above are considered the most common causes of PFPS. However, psychosocial factors may also contribute to the pain. Anxiety, depression, catastrophizing (thinking things are much worse than they are), and kinesiophobia (fear of movement) may also contribute to the anterior knee pain of PFPS. It is not common for these psychosocial factors to produce pain on their own, but any combination of biomechanical and psychosocial factors should be considered in a complete evaluation.

Assessment

The evaluation of PFPS begins with a thorough client history. The most common complaint is pain felt with jumping, running, or climbing and descending stairs. Pain is also likely when the knee remains flexed for long periods, such as a long car ride or sitting in a movie theater. As noted earlier, the client may also complain of grinding or grating sensations of the patella during knee flexion or extension movements. You can place your hand lightly on the patella as the client is seated on the edge of the table and move the knee through flexion and extension. Not much pressure on the patella is needed to feel these grinding sensations.

The tissues surrounding the patella, especially the quadriceps retinaculum, may be tender when palpated. You can palpate them with the knee in full passive extension on the treatment table and when the knee is moving through flexion and extension. Greater tensile loads are on the retinacular tissues during motion, and this increases sensitivity during palpation.

It may also be helpful to grasp the patella between your fingers and move it from side to side (Image 5). Ideally, the patella should move about half its width to each side. It is not necessarily pathological if it does not move much, but note if significantly restricted. Especially, note if it moves easily in a lateral direction but does not move much in a medial direction. This would indicate tightness in the lateral restraining tissues. Also, connective tissue fibers from the iliotibial band extend into the lateral retinaculum around the quadriceps. So, tightness transmitted through the iliotibial band from the hip abductor and gluteus maximus muscles could also play a role in improper patellar tracking.

Image 5

Lateral movement of patella

There are several special orthopedic tests commonly used to evaluate PFPS. However, in recent years their accuracy has been called into question.3 It appears that a comprehensive history in conjunction with some basic physical examination procedures are still the most accurate means of identifying the problem.4 The most helpful physical examination factors include:

- Pain around the patella with palpation

- Increased pain during palpation with the extensor muscles under load (such as palpation during a partial squat)

- Pain with squatting or going up or downstairs

Keep in mind that other problems around the knee may have similar signs and symptoms. These conditions include patellar tendinosis, joint pathology, plica syndromes, Osgood-Schlatter’s disease, or pain from peripheral nerve or nerve root compression.

Treatment

The most common treatments for PFPS are conservative and noninvasive. In traditional orthopedic treatments, patellar taping and bracing are common. They seem to be more effective in the short term as opposed to with more chronic cases. Improving strength balance within the quadriceps is also a core component of physical therapy treatment.

Massage can clearly play a role in treating patellar tracking disorders, especially in reducing hypertonicity of the tissues around the patella. Reducing hypertonicity helps restore muscular balance. The soothing effects of gliding massage strokes on a painful knee should not be undervalued either. Effective approaches may combine techniques with a broad context surface such as the full palm or hand, along with more specific stripping techniques using the thumb, finger, or perhaps a pressure tool. I have also found performing these techniques during active movement of the knee enhances their effectiveness. You can see an active engagement technique for the patellar retinaculum in this video.

Conclusion

Anterior knee pain is a common complaint for numerous clients. It is likely to occur with any individuals engaged in high activity levels. Understanding the biomechanical role of the patella and surrounding tissues can help you target your treatment for the best results. Developing a better understanding of patellofemoral function also illustrates an excellent opportunity for you to work with other health professionals to achieve the best results for the client.

Resources consulted:

- Hott A, Brox JI, Pripp AH, Juel NG, Liavaag S. Predictors of Pain, Function, and Change in Patellofemoral Pain. Am J Sports Med. 2020;48(2):351-358. doi:10.1177/0363546519889623

- Rothermich MA, Glaviano NR, Li J, Hart JM. Patellofemoral pain. Epidemiology, pathophysiology, and treatment options. Clin Sports Med. 2015;34(2):313-327. doi:10.1016/j.csm.2014.12.011

- Nunes GS, Stapait EL, Kirsten MH, de Noronha M, Santos GM. Clinical test for diagnosis of patellofemoral pain syndrome: Systematic review with meta-analysis. Phys Ther Sport. 2013;14(1):54-59. doi:10.1016/j.ptsp.2012.11.003

- Willy RW, Hoglund LT, Barton CJ, et al. Patellofemoral pain clinical practice guidelines linked to the international classification of functioning, disability and health from the academy of orthopaedic physical therapy of the American physical therapy association. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2019;49(9):CPG1-CPG95. doi:10.2519/jospt.2019.0302