Technique Isn’t Enough: The Importance of Clinical Reasoning

- Whitney Lowe

Updated 11/30/2023

The Issue

In the massage profession, you’ll find a wealth of courses teaching new techniques. Clearly, learning new techniques can enhance your skills and abilities, giving you more ways to address client problems. However, for orthopedic pain and injuries, the emphasis on techniques can be misleading. Even with simple conditions, the treatment technique is only one piece of the therapy. Clinical success in treating pain and injury conditions requires more comprehensive knowledge and a developed skillset that goes beyond the treatment toolbox.

In a recent post, I discussed the ongoing problem of how we refer to the broad types of massage in our profession. I mentioned clinical, medical, and also orthopedic massage. Regardless of what one might call it, those treating pain and injury conditions have a high bar for getting their clients out of pain. In my work, I’ve referred to what I do as orthopedic massage to reflect how mainstream medical care categorizes the care of movement oriented pain and injuries, which is orthopedics. In treating orthopedic conditions, whether massage, physical therapy, or surgery, a general protocol is followed of assessment and treatment.

In the first year of my practice, I rented space in a medical office building and began networking with the physicians working there. One day a physician sent a patient to me who had severe back pain. I realized as I began talking to her that I had no idea what was wrong with her and had no idea whether massage would help or hurt her. I’d taken a load of new technique workshops, but they hadn’t taught me how to make important clinical decisions, like figuring out what a client’s issue might be, how to gauge its severity, and know if massage was contraindicated. Without that, I wouldn’t know what treatments to pursue.

I wanted the referring physician to respect massage as a beneficial treatment approach, so I felt uncomfortable sending the client back to the doctor and telling him I didn’t know if I could help or not. It was at that point I realized I needed to learn more about clinical management and evaluation. Further, as I took more physician and physical therapy referred clients, it became clear that sometimes those providers also didn’t really get what was going on. What I realized in these situations was that what I really needed was to be competent in evaluating a problem. That I needed to go beyond the learning of massage techniques.

In my career of 35-plus years, I have focused on developing those other skills and the knowledgebase that undergirds pretty much all that goes into treating pain and injuries. First, one needs a system and comprehensive approach to evaluating these potentially complex problems. Second, one has no choice but to develop well-honed clinical reasoning skills.

And therein lies the secret to being a stellar orthopedic (or clinical massage or medical massage) soft-tissue therapist. A wide variety of techniques are applied in this approach. But, without effective evaluation, wise decision-making, and informed clinical reasoning, we simply cannot really know what tissues need treating, why we would treat them, and which protocols best fit the problem.

Clinical Reasoning is Key

Clinical reasoning is at the core of all successful clinical practice in the healthcare professions. Yet, it can still be missing in practice because it’s much easier to launch into using a sexy new technique. Simply put, clinical reasoning is “…the sum of the thinking and decision-making processes associated with clinical practice.”1 The more effective you are at clinical reasoning, the more effective and successful you will be as a practitioner.

Developing effective clinical reasoning is not as simple as just taking a course in it. It is a more complex process that calls upon your skills and abilities in a variety of different areas. Let’s take a look at how to improve those skills.

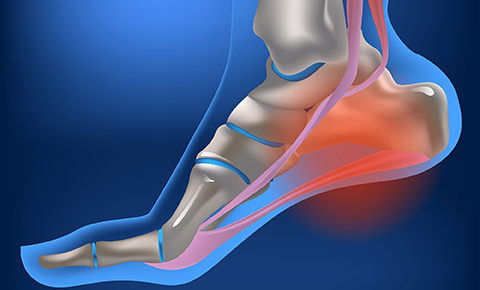

Researchers have found that what separates experts from novices in medical clinical management skills is that experts develop certain shortcuts by recognizing information that novices might miss.2 For example, suppose a client comes in complaining of foot pain and reports a recent increase in running on hard pavement and plantar foot pain that is most pronounced first thing in the morning. With just two clinical factors, someone familiar with plantar fasciitis might immediately recognize them as possibly fitting into that pattern.

Recognizing patterns, however, does not mean that we can determine a client’s problem with just a couple of symptoms. Far from it. In fact, jumping to conclusions and making assumptions about a client’s condition is a sure-fire way to make critical treatment mistakes. Taking the above two symptoms as an example, mistaking a Baxter’s neuropathy with plantar fasciitis can lead to the client suffering for years, if not permanently. The orthotics often prescribed, along with massage therapy, can further compress the nerves impinged in Baxter’s neuropathy.

Yet, the ability to see the symptom pattern gives us a significant advantage in knowing how to progress in assessment and then treatment. The practitioner using effective clinical reasoning, takes the recognized patterns and applies deductive thinking to analyze the problem further. Deductive logic is what occurs with “if, then…” thinking. For example, IF this client reports sharp shooting pain in the upper extremity along with paresthesia on the ulnar aspect of the hand, THEN there is a good chance the pain complaint is originating from some neural pathology in either the neck or upper extremity. This deductive analysis helps us determine the ‘what, why’ of the client’s problem and then the ‘which and how’ of the treatment.

Clinical reasoning is crucial not only in clinical assessment but in treatment as well. Treatment recipes and routines are given that describe how to address a particular pathology. That’s ok, if these routines are used as examples that inform, but not direct, your treatments. If these are taken as guidelines, not fixed directions, then having the protocols in your treatment toolbox is fine. It is then your job to customize any protocol – through the evaluation process – to fit the unique and individualized presentation of a client’s pain or injury.

A caveat to prescriptive protocols is to be able to recognize when those are extravagant claims that tout magical recoveries or permanent, overnight success. Each client is an individual, and each has a unique presentation of his or her soft-tissue disorder. One person’s carpal tunnel syndrome may need to be treated quite differently than another person’s, even though they may have been diagnosed with the same disorder. It is your use of clinical reasoning and decision-making skills that help you determine how to modify your treatment for each client’s needs.

As with many aspects of health care delivery, clinical reasoning relies on both art and science. You need a comprehensive understanding of science (anatomy, physiology, kinesiology, etc.) to help in symptom pattern recognition, creating a proper rehabilitative protocol, and treatment strategies. Using effective clinical reasoning is an art and skill that is developed with constant practice and study.

Treatment techniques will help you fill your tool bag, but if all you do is amass a series of techniques, you only have a bag of tools. A wrench is a great tool, but you don’t want to try using a wrench when a screwdriver is the proper tool. Similarly, you will be far more successful and your massage skills will have greater effect when you expand your use of effective clinical reasoning.

We have put great emphasis on the importance of developing clinical reasoning skills in our online programs. The structure of the course content in a condition specific format is a great benefit in developing those skills. You can learn more about our comprehensive orthopedic and clinical massage courses here.

- Higgs J, Jones M, Loftus S, Christensen N. Clinical Reasoning in the Health Professions. 3rd ed. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2008.

- Epstein RM, Hundert EM. Defining and assessing professional competence. Jama. Jan 9 2002;287(2):226-235.