Exploring Charcot Marie Tooth Disease

- Whitney Lowe

A description of Charcot Marie-Tooth disease, a systemic nerve condition often mistaken for local nerve compression problems, and how to assess and treat it.

Introduction

The longer you stay in practice, the more likely it is that you will encounter a wide array of compromised health conditions that your clients present with. Sometimes a case that might look like a simple tendinosis or common carpal tunnel syndrome is exactly what it seems. But don’t get caught in that trap! Often what might look like a common or familiar problem on the surface may be something very different. For example, systemic nerve conditions are often mistaken for local nerve compression problems because the symptoms can be quite similar.

Charcot-Marie-Tooth (CMT) disease is a perfect example of a systemic disorder that can masquerade as one or several nerve compression pathologies. While this condition may sound like a dental issue, it is actually a hereditary neurological disease named after three physicians living in 1886—Jean-Martin Charcot, Pierre Marie, and Howard Tooth. CMT is a genetically inherited disorder and does not result from overuse or mechanical nerve compression like many other common nerve problems. Although it is a genetically inherited disorder, generation skipping is not uncommon. It is a fairly common neurological disorder estimated to affect about 125,000 people in the U.S. alone. It is about as common as multiple sclerosis (MS) or amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS or Lou Gehrig’s disease). However, because CMT is not life-threatening, we don’t hear about it as often.1

This pathology may sometimes go by other names as well. It is often called hereditary motor and sensory neuropathy. It is also referred to as peroneal muscle atrophy; however, this nomenclature can be a little misleading. Several of the sources that describe this condition as peroneal muscle atrophy cite a drop-foot gait as the most significant early indicator of the condition, and ascribe the drop-foot gait to peroneal muscle atrophy. However, a drop-foot gait occurs when there is inadequate nerve supply to the dorsiflexor muscles of the foot. Although the small and sometimes absent peroneus tertius muscle is a dorsiflexor, the primary peroneal muscles (peroneus longus and brevis) are plantar flexors, and therefore atrophy in these muscles does not produce the drop-foot gait.

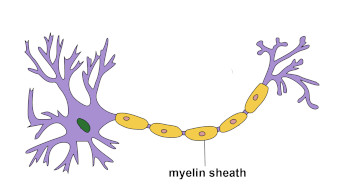

CMT is usually divided into two predominant types, although recent clinicians have further divided these types into other subgroups. Type 1 is a neuropathy (pathological condition of the peripheral nerves) that occurs from demyelination of the nerve fiber. Nerve fibers in most of the peripheral nerves are covered by a myelin sheath, and it is the myelin sheath that is essential for proper transmission of the neurological signal (Figure 1). In type 1 CMT there is a mutation in the myelin structure that causes it to become unstable and spontaneously break down. When the myelin breaks down, it is not able to transmit neurological signals properly.

Figure 1

The myelin sheath of a typical nerve

Image courtesy of Wikipedia

Type 2 CMT is not a demyelinating disorder, but rather a neuropathy that occurs from what is called wallerian degeneration. The process of wallerian degeneration involves not only a breakdown in the myelin structure on the outer surface of the nerve fiber, but also destruction in the continuity of the axon. It is difficult to determine which type of CMT a client has without more specific laboratory evaluation procedures.

EVALUATION AND TREATMENT

One of the most problematic features for assessment of a condition such as CMT is the similarity of its symptoms to other peripheral nerve pathologies. For some reason, symptoms are usually perceived first in the distal lower extremities. It was mentioned earlier that the peroneal muscles are often affected. CMT appears to have the most significant effect on muscles innervated by the deep and superficial peroneal nerves. In this condition, the motor effects of nerve fiber disruption are much more significant than the sensory effects. Therefore, important symptoms to watch for include muscle weakness and lack of coordination rather than numbness or paresthesia. However, this may also be true for other compression neuropathies of the common peroneal nerve. Disruption of signals to the dorsiflexors of the foot is frequent, and that is the reason that foot drop is a common symptom.

Symptoms of CMT usually occur during the second decade of life and may initially present as a general awkwardness or clumsiness, especially in the lower extremities. This is commonly a period of awkwardness for many adolescents as they are growing, so detection is often not made early in development. Motor nerve damage resulting from CMT commonly progresses with age so the condition frequently gets worse as the person gets older.

It is common for clients to develop a pes cavus foot (excessively high arch, shown in Figure 2) as well as hammer toes. Observation of the leg will often indicate thin, “stork-like” legs due to visible muscle atrophy. The client is often able to walk on tip toes (primarily using the plantar flexor muscles), but will have great difficulty walking on his or her heels (primarily using the dorsiflexor muscles). The clinician should also take a detailed and thorough history because certain medications and even vitamins in high dosages may cause an aggravation of CMT symptoms.1

Figure 2

The pes cavus foot that is common in CMT disease

Image courtesy of Wikipedia

As mentioned earlier, most of these muscular symptoms appear in the lower extremity first, although some may appear in the upper extremity as well. When symptoms affect the upper extremity, the client primarily displays motor effects. S/he will usually report difficulty in operating zippers, buttons, or doing precise movements with the hand.

There is no current cure for CMT, although it is most commonly managed with conservative treatment that is aimed at stabilizing symptoms. Conservative treatments like physical therapy or orthotics are used to address the motor dysfunction in the lower extremities. In some cases, surgery is used to address more severe foot alignment problems like the severe pes cavus foot. However because motor function may continually change with progressive degrees of nerve damage, surgical procedures may have limited effects. If the biomechanical alignment problem is changed with a surgical procedure and then motor function continues to alter with further nerve damage, the alignment in the foot may be changed rendering the surgical intervention less effective.

Due to the nature of this problem, it is not one that is likely to be corrected by massage therapy. Massage might be used to treat various distal extremity neuropathies and it may appear that there is some type of compression neuropathy occurring, when in fact the client has a hereditary neurological problem that cannot be corrected with physical intervention such as massage. There is no evidence that massage is harmful for CMT but, in the best interest of finding the true source of a client’s complaint, it is valuable to know about this condition and consider it as a possible cause for the client’s symptoms. If there is evidence that CMT may exist it is important to refer the client to a physician for evaluation.

Resources

- Stadler T, Ross D. Charcot-Marie-Tooth Disease in a High School Tennis Player. Phys Sportsmed. 2002;30(10).