Simple Guide to Trigger Finger Treatment

- Whitney Lowe

One of the more debilitating conditions in the hand is trigger finger. In this painful condition, the tendons of the finger or thumb cannot bend or straighten smoothly due to thickening, swelling, or nodules in the tendon, its synovial sheath, or the connective tissue bands around the finger. Trigger finger can be an overuse syndrome or a result of another systemic, often metabolic, problem.

Trigger finger can be incapacitating and painful. When the symptoms are recognized earlier, less invasive treatment can be successful and prevent the need for surgery. This condition is something your clients may experience, but it can also be a severe work-limiting injury for you!

Anatomical Background

Think about any grasping or precision movement of the hand. A complex interplay of structure and function is necessary to make any of those movements. Treating trigger finger starts with understanding the unique system of tendons and connective tissues in the fingers and thumb that act like ropes and pulleys. Grasping objects requires the joints to bend in flexion. The finger and thumb flexor tendons run along the anterior surface of the fingers or thumb. These tendons are tethered close to the bones by connective tissues called pulleys. In the fingers, pulleys are found at eight locations from the metacarpophalangeal (MCP) joints to the distal phalanges.

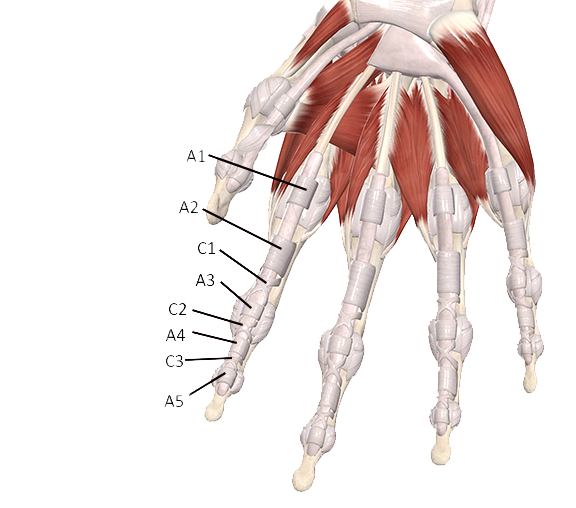

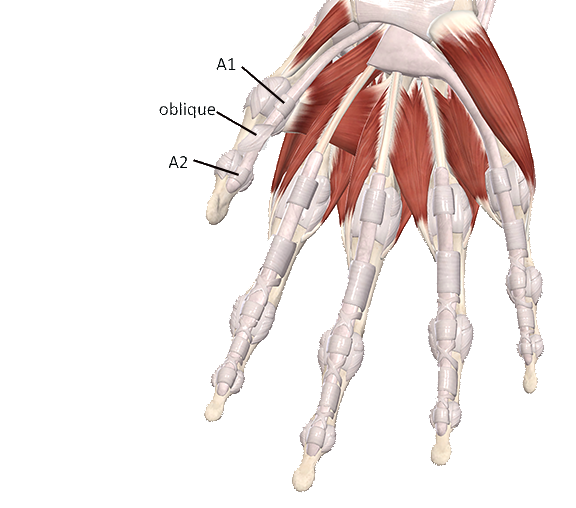

The thumb is generally considered to have three primary pulleys, although recent studies describe a fourth pulley in the thumb.(1) There are five pulleys in the fingers, called annular pulleys, named A1 through A5 (Image 1). The A1, A3, and A5 pulleys are smaller and considered minor pulleys (primarily due to size, not importance). The A2 and A4 pulleys are larger and are sometimes called the major pulleys. The A1, A3, and A5 pulleys are located at the MCP, PIP, and DIP joints, respectively. The A2 and A4 pulleys are located in the middle of the proximal and middle phalanx, respectively (Image 1). The thumb has three primary pulleys; the A1 and A2 pulleys are like those of the fingers, and an oblique pulley sits between them (Image 2).

In the fingers, a second set of connective tissue pulleys, called cruciate pulleys, give additional support and stability to the tendons. The term cruciate means cross; you can see by their structure where they get their name (Image 1). The cruciate pulleys are much smaller than the annular pulleys. There are three cruciate pulleys designated as C1, C2, and C3. Their role in improving the flexor tendon’s angle of pull is insignificant, so finger movement is not impaired as much if they are involved.

With all these connective tissues crossing over the tendons, there is significant friction between the tendon and the pulleys. The tendons are enclosed in a synovial sheath to reduce that friction. The sheath is in contact with the connective tissue pulleys, and the tendon slides back and forth inside the sheath so it does not rub against the pulleys. However, tendon and synovial sheath pathologies may still develop from excessive friction or other factors. Trigger finger/thumb is one of these conditions.

Pathophysiology

Trigger finger is also called stenosing tenosynovitis. The term stenosing means narrowing and refers to the narrowing of the space for the tendon inside the sheath due to fibrous adhesion and inflammation. Tenosynovitis refers to inflammatory irritation between the tendon and the surrounding synovial sheath. Stenosing tenosynovitis develops because of excess irritation between the finger’s tendon, sheath, and flexor pulleys.

Trigger finger generally develops when inflammation and swelling occur at the interface between the tendon and one of the pulleys, usually at the A1 pulley. Inflammation occurs in the tendon, the sheath, the connective tissue pulley, or a combination. The thickening prevents the tendon from gliding smoothly through the pulley, resulting in pain, limited movement, and strange clicking sensations.

A fibrous nodule can also develop on the tendon that prevents the tendon from sliding underneath the pulley. With force, the nodule can pop underneath the pulley. The sudden motion and popping of the tendon nodule are like pulling a trigger; this is how the condition gets its name. It is usually quite painful when the nodule pops back and forth under the pulley.

There is about a 3 to 1 ratio of females to males who develop this condition, and it is most common in people in their fifties and sixties.(2) It is more frequent in the thumb and ring finger, though it also occurs in the index finger and long finger. People are more likely to develop this condition in their dominant hand, which strengthens the idea that some of the problem may be related to chronic overuse and physical load on the finger tendons. Forceful gripping, blunt trauma, or repetitive finger/thumb movements can also lead to the condition. It affects about 2-3% of the general population.

In addition to biomechanical causes, trigger finger is also correlated with various metabolic conditions, particularly diabetes. It affects up to about 10% of that population.(3) Other metabolic challenges that can play a prominent role in its development include rheumatoid arthritis, Dupuytren’s contracture, osteoarthritis, de Quervain’s tenosynovitis, osteoarthritis, hypothyroidism, and carpal tunnel syndrome. The nature of the relationship of these conditions to trigger finger is not very clear, other than they all involve systemic inflammation. Trigger finger/thumb can be a combination of biomechanical or metabolic factors. You can learn much more about these various hand conditions in our course: Orthopedic Massage for the Elbow, Forearm, and Hand.

Assessment

Assessment is based primarily on the client’s history and a detailed clinical examination. Ultrasound may be used to measure the thickening of the affected tendon sheath. Clients with trigger finger will report pain and stiffness, with limited flexion of the finger or thumb. Fully straightening the digit may hurt, and there may be popping or grating sensations with movement. If the condition is advanced, the joint may get stuck in flexion or extension and may not bend or straighten. The metacarpophalangeal (MCP) joint may also be tender.

In the history, ask about existing metabolic challenges such as diabetes, hypothyroidism, rheumatoid arthritis, or any other metabolic factors. There may not be evidence of specific overuse but ask about significant increases in biomechanical stress of the fingers or thumb.

Swelling, a bump, or protrusion may be palpable if a tendon nodule has developed. If the condition is in one hand only, you will feel the difference in size between the affected and unaffected side. It may be challenging to make this comparison if both sides are involved, but enlargement around the joint is common. The area where the tendon nodule has developed is also likely to be painful with palpation. Use caution when applying pressure, as the pain can be intense.

Both passive or active flexion and extension are likely to be painful. Active movement may be more painful because of the greater load on the affected tissues. There may also be pain during resisted finger flexion or extension (manual resistive tests) if a nodule is pulled against the connective tissue pulley. In most cases, a nodule and restriction will be on the palmar side of the fingers, so flexion is affected more than extension. If the condition is advanced, the finger may be stuck in partial flexion or extension. It is also common for the client to report grating sensations (crepitus) during finger or thumb movements.

Traditional Treatment

Conservative modalities are the preferred treatment for trigger finger. Unfortunately, there are no firmly established conservative treatments that show high success. Treatment usually begins with splinting the affected joint region to decrease the load on the tendon. Restricting movement is crucial to keep from overloading the tendons and increasing inflammation. Fibrous adhesions between the tendon, sheath, and pulley are factors in the condition’s perpetuation. Gentle movement within the tolerable range is encouraged to prevent additional tissue adhesion. Heat will increase tissue pliability and ease pain; ice may also help with pain.

Orthopedic Medical Massage Treatment

Various types of massage may be helpful in the early stages before significant tendon nodules and fibrous adhesions develop. The primary benefit of direct massage in these early stages is to help encourage full pliability and mobility of the tendons within the connective tissue sheath. Friction massage promotes appropriate slide and glide between adjacent tissue. They are used to treat tenosynovitis and tendinosis as well since they reduce adhesions between adjacent tissues and encourage mobility.(3)

Perform soft-tissue treatments within the client’s comfort and pain tolerance. In addition, teaching the client self-massage techniques (usually friction and mobility strategies) on the affected area is helpful because they can do this in just a few minutes, several times a day. Friction techniques are more effective when performed regularly rather than weekly, so client education and self-massage strategies are critical to therapy. Various other techniques designed to encourage tissue mobility and relaxation are also helpful when applied to the flexor and extensor muscles of the forearms, as the affected tendons are coming from these muscles.

If initial conservative treatments are ineffective and the condition is in its early stage, corticosteroid injection is the subsequent treatment usually attempted. These can have several sometimes problematic side effects. Other treatments include shockwave therapy and surgery. Be sure clients have a physician investigate potential metabolic and systemic issues that could be the cause.

Conclusion

Trigger finger can be a debilitating and painful condition. Massage therapists and others who work with their hands should be aware of this condition because it can impair their ability to use their hands. No gold standard for effective treatment exists, so conservative options are sought first. There is an excellent physiological argument for why massage, mobility, and safe, protected movement can all work together, especially in the early stages, to prevent the condition from developing further. Orthopedic medical massage and soft-tissue strategies can potentially reduce healthcare costs, long-term impairment, and the need for invasive procedures.

Resources

- Zafonte B, Rendulic D, Szabo RM. Flexor pulley system: Anatomy, injury, and management. J Hand Surg Am. 2014;39(12):2525-2532. doi:10.1016/j.jhsa.2014.06.005

- Vasiliadis A V., Itsiopoulos I. Trigger Finger: An Atraumatic Medical Phenomenon. J hand Surg Asian-Pacific Vol. 2017;22(2):188-193. doi:10.1142/S021881041750023X

- Matthews A, Smith K, Read L, Nicholas J, Schmidt E. Trigger finger: An overview of the treatment options. J Am Acad Physician Assist. 2019;32(1):17-21. doi:10.1097/01.JAA.0000550281.42592.97

- Dala-Ali BM, Nakhdjevani A, Lloyd MA, Schreuder FB. The efficacy of steroid injection in the treatment of trigger finger. Clin Orthop Surg. 2012;4(4):263-268. doi:10.4055/cios.2012.4.4.263

- Yildirim P, Gultekin A, Yildirim A, Karahan AY, Tok F. Extracorporeal shock wave therapy versus corticosteroid injection in the treatment of trigger finger: A randomized controlled study. J Hand Surg Eur Vol. 2016;41(9):977-983. doi:10.1177/1753193415622733