Tracking Anterior Knee Pain

- Whitney Lowe

An overview of the structural and mechanical issues often causing anterior knee pain, and how to identify and address these issues with massage.

Introduction

How many times have you heard someone say “Oh my aching knees?” It happens with frequency among athletic populations, but just as frequently plagues individuals who are not highly active. Unfortunately, people may have their condition dismissed and told it is just arthritis and they can live with it or perhaps take anti-inflammatory medications. Yet in many cases anterior knee pain is a soft-tissue problem that involves complex biomechanics of the knee that are not thoroughly evaluated and could be effectively treated with soft-tissue approaches like massage. A deeper look at these structural and mechanical issues helps in developing a better plan for using massage in addressing anterior knee pain.

Key Structures

There are several key anatomical structures that play a role in anterior knee pain. The quadriceps muscle group has the primary role of producing the power of knee extension for locomotion. Knee pain doesn’t usually derive directly from the quadriceps muscle bellies. More often dysfunction lies in the distal tendon of the quadriceps muscles or the other connective tissues that connect the muscle group to the tibia.

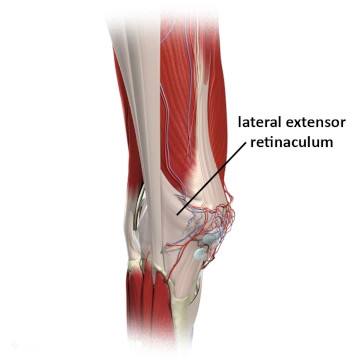

The majority of quadriceps fibers attach to the tibia by way of the patellar tendon. However, the connection of the quadriceps with the tibia is not limited to the patellar tendon alone. The quadriceps retinaculum, also called the extensor retinaculum, has a key role in helping transmit the contraction force of the muscles to the distal tibia (Figure 1). The retinaculum is often overlooked as a pain producing tissue, but it is frequently the cause of anterior knee pain when patellar tracking disorders are present, which are discussed below.

Figure 1

Lateral quadriceps retinaculum

3D anatomy images. Copyright of Primal Pictures Ltd. www.primalpictures.com

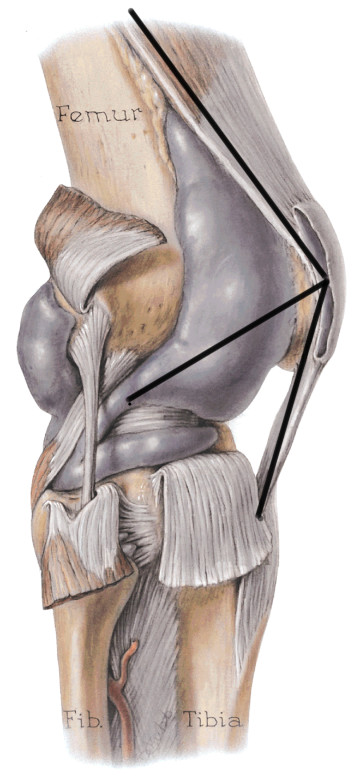

The patella is another structure that is crucial to knee function, but often misunderstood. It is commonly thought that the primary function of the patella is to protect the knee. But that’s not really its role. Its primary function is to improve the power of the quadriceps. Because the patella is embedded within the patellar tendon, it acts like a fulcrum to pull the tendon farther away from the joint’s axis of rotation making the quadriceps group more powerful (Figure 2).

Figure 2

Mechanical function of the patella

Mediclip image copyright (1998) Williams & Wilkins. All Rights Reserved.

Biomechanics and tracking disorders

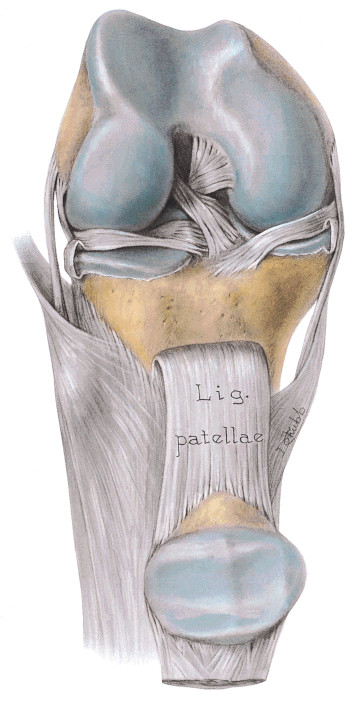

The patella has a ridge on the underside of it and this ridge fits in the groove between the two femoral condyles (Figure 3). As the knee moves in flexion and extension the patella tracks in a superior and inferior direction. The ridge of the patella must stay centered between the femoral condyles for proper knee mechanics.

Figure 3

Patellar ridge fitting between femoral condyles

Mediclip image copyright (1998) Williams & Wilkins. All Rights Reserved.

Unfortunately, in many cases the patella does not track straight up and down in the groove. Muscle imbalance and other alignment factors such as a large Q angle can lead to problems in correct patellar tracking. When the patella is tracking incorrectly it is most commonly pulled in a lateral direction. This is called a lateral tracking disorder.

If not corrected, tracking disorders in the patella can cause long-term degeneration of the knee. If the patella is being pulled to one side it causes excess friction between the underside of the patella and the femoral condyles. The excess friction produces a softening and degeneration of the articular cartilage on the underside of the patella, which is a condition called chondromalacia patellae.

Tracking disorders of the patella cause anterior knee pain, but there is still some controversy as to which tissues are the source of the primary pain. For example, it was once thought that tracking disorder pain was caused by the cartilage degeneration of chondromalacia. However, the articular cartilage has very little innervation, so it is unlikely that cartilage degeneration is a primary source of knee pain. The layer of bone just underneath the articular cartilage is called subchondral bone. It is richly innervated and it is likely that tracking disorder pain may result from damage that has extended all the way to the subchondral bone.

There is another likely explanation for anterior knee pain resulting from tracking disorders that does not appear as frequently in much of the orthopedic literature. The patellar retinaculum and other connective tissues that help attach the quadriceps to the tibia are also richly innervated. An imbalance of tensile forces on these retinacular tissues can cause anterior knee pain in the soft tissues.

An effective way to identify if the retinaculum and other extensor mechanism connective tissues are a key factor in the anterior knee pain is to stress these tissues while palpating them. The most effective way to do this is to perform a resisted knee extension and palpate with moderate to deep pressure all of the connective tissue structures around the knee while the contraction is held. This same procedure could be done by engaging an eccentric contraction of the quadriceps muscles while these structures are being palpated. The eccentric contraction has the tissue being lengthened at the same time it is being deeply palpated, which exaggerates the stress on the tissue and makes it easier to identify problem areas.

Treatment strategies

Many tracking disorders originate from imbalance in the pulling forces between the different quadriceps muscles. Massage can be a highly effective means of helping to restore normal biomechanical balance in the knee. Unfortunately, it is greatly underutilized in the traditional rehabilitation community for addressing this problem. Invasive techniques such as cutting the lateral retinaculum surgically so it doesn’t pull the patella so far laterally are often used before all conservative measures been attempted.

Massage treatment can be very helpful in balancing the excess pull from the lateral side of the patella. Once the key areas of tightness and sensitivity have been identified they can be addressed with very specific stripping techniques and those involving active engagement as well. By applying deep specific elongation techniques with a small contact surface like a thumb, fingertip, or pressure tool, the practitioner is able to provide a highly specific treatment strategy that is more focused than many of the other general approaches such as relying only on strengthening techniques to restore balance in the region.

Conclusion

Many practitioners have shown and demonstrated excellent clinical results with soft-tissue treatments for tracking disorders. Now we need to compare those treatments with more traditional methods and see if they are clinically effective across the board. If they are found to be more successful, and it is likely that they would be, there would be a greater body of supporting evidence to encourage a different treatment approach that includes massage.